William Douglas was born in Tennessee around 1800 and appears to have made his way to Buffalo by the 1830s. It is not known if Mr. Douglas escaped from slavery or was freed. Once in Buffalo, he became an independent businessman whose customers were mostly African-American sailors, canal boatmen and dock laborers.

Dug's Dive was one out of hundreds of saloons, boarding houses and brothels near the docks that provided entertainment, sustenance, and physical companionship to men who landed at the Port of Buffalo. Uncle Dug, as Mr. Douglas was known, offered food, drink and shelter to black men and women for more than 20 years.

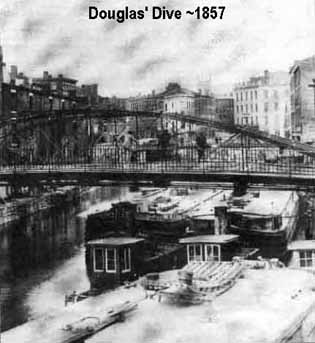

Dug's Dive was located in the basement of the Union Block, a narrow triangle sandwiched between the Commercial Slip of the Erie Canal and Commercial Street, just north of the Water Street bridge. Aboveground, the Union Block appears to have been composed, at the beginning, of discrete, multi-story units, somewhat like a rowhouse. Dug's Dive, however, seems to have occupied the continuous basement beneath.

Above the basement level, the Union Block was three stories high. It contained several African American residences and businesses, including a mixture of saloons, brothels and hoarding houses. For this reason, the block was also known as the "Negro Block."

Uncle Dug's basement saloon was entirely below the level of Commercial Street, and could be reached only from the "back," or canal side, like a house or barn tucked into a hill. The land had naturally sloped to the watercourse of Little Buffalo Creek. (Adapting buildings to slopes in this manner is common. When the Commercial Slip was filled in in the 1920s, the natural slope and the man-made terracing that followed was lost below a uniform grade across the site.)

There was no official street address, the 1855 city directory listing the location of Dug's Dive as a "recess" at the corner of Commercial and Water Street. Later directories list various numbers on Commercial Street or just "Union Block- Commercial Slip."

In this view taken between 1855 and 1862, The Union Block, or "Negro Block", stands on the left, behind the bridge in foreground. Its basement borders the towpath of Commercial Slip, the terminus of the Erie Canal. The Negro Block was known as such because it housed many African-American - owned businesses, including Dug's Dive, which could only be entered from the towpath. A State project would destroy the site good chance that the actual walls of Uncle Dug's place still stand.

According to an 1874 newspaper article, the way to get to Dug's Dive was to go down the Water Street bridge stairs onto the towpath and then to head north twelve to fourteen feet. Once you found the door, you still had to go four or five steps below the towpath to get into Uncle Dug's place.

Being below the streets and even below the canal towpath, the inside of the saloon was generally described as damp and unsanitary. The basement of the Union Block would occasionally flood when storm surges raised lake water levels, and Uncle Dug openly talked of how he expected his end would come from drowning.

Newspaper articles of that period describe Dug's Dive as a rundown place where a man of normal height could not stand erect. There is no doubt physical conditions were appalling by today's standards. Even under these poor conditions, though, Dug's Dive was regularly filled, some eating, drinking and socializing, while others slept on benches in the bar, the kitchen and the "parlors," as Uncle Dug called his boarding rooms.

In many ways, Uncle Dug's place was no different than all of the Dives in the area. In one way, though, William Douglas's establishment was different He was known as a good Samaritan for giving food and a place to sleep to African-American in need of help who found his door. Undoubtedly, these unfortunate souls included many fugitive slaves finding their way to Canada with nothing but the shirts on their backs.

Practically every clump of Negro settlers in the free states was an Underground depot by definition, for the runaway considered a black skin an even more reliable promise of help than a Quaker. So, it seems logical to assume fugitive slaves found refuge in Dug's Dive, along with many of the other establishments in the Union Block. For Buffalo, this "Negro Block" would have been especially important, with runaways arriving regularly down at the wharves by ship and overland, each needing to quickly find assistance [see William Wells Brown].

Refuge was a life or death matter in Buffalo's African American community during the 1850s and early 1860s. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed (under the Administration of Buffalonian Millard Fillmore, who ironically owned property a cobblestone's throw away on Hanover Street, also to be destroyed by the state project), long-settled blacks up north were faced with the possibility that they could be dragged hack to slavery, and any person helping them could be criminally implicated.

Particularly at risk were runaway slaves who worked on boats traveling the Great Lakes, never knowing who might he waiting on shore at any port of call.

One example was Buffalo's own fugitive slave case of 1851, wherein a man named Daniel Davis, working on a Lake Erie steamer, was arrested at the dock at the foot of Commercial Street (where in later years the Canadiana, the "Crystal Beach Boat," was docked) within two hundred feet or so of the Union Block. Following an initial magistrate's ruling that he must be returned, Mr. Davis was released by a federal judge in Auburn, NY on a technical interpretation of the law. Evidently not wanting to test his luck or the law further, Davis then made his way to Canada.

With the ever-present threat of capture, fugitive slaves on ships calling at Buffalo would likely seek out convenient yet obscure places like Dug's Dive, in the midst of, yet apart from, Buffalo's bustle.

In Midst of Civil War Tensions, a Redoubt During Riot of 1863

Dug's Dive also was a sanctuary for many during a violent riot on (he docks on July 6, I863, culminating a tense spring and summer. The nation was in the midst of civil war, and the President Lincoln was implementing an unpopular draft.

New York Governor Horatio Seymour, a Democrat, had taken office earlier in the year, saying the Jan. 1. I863 Emancipation Proclamation was a violation of the constitution, that carrying out the liberation of 4,000,000 slaves Would require the North to resort to military despotism. These words reflected great tensions, coming from the leader of the most populous and prosperous state in a time of national crisis.

All spring, Army enrollers went house to house across the city, seeking able-bodied men between 20 and 45. Physical and family exemptions could be had, but also, upon payment ,of $300 cash, a man could designate a substitute to go to war for him.

As only the rich had recourse to $300 in ready cash, the poor viewed this as a class war.

()n July 4th, I863, Governor Seymour told an Independence Day audienceójust getting news of the Battle of Gettysburgó that the country was an the "very verge of destruction" because of government coercion, "seizing our persons, infringing upon our rights, insulting our homes...men deprived of the right by trial by jury, men ton from their homes by midnight intruders." Seymour's speech, and a similar one delivered by former President Franklin Pierce, was widely disseminated by the newspapers.

These sentiments, filtered down to the burgeoning foreign- born population, 50% of whom were Irish, became simplified s a rich man's war and a poor man's fight. The slaughterhouses of Shiloh, Bull Run, and Antietam were not the best recruiting tools, and the draft, a military necessity, was politically and socially divisive.

In this climate, on July 6th, a fight broke out on the Buffalo docks. A mob coalesced, and the fight quickly escalated to the point where hundreds of Irish dock workers attacked blacks at random. At least two blacks died.

When the rioters decided to "clean out" the Union Block, a mob quickly surrounded the building. A large force of police fought their way in and rescued a large number of men from "the Douglas dive" who were taken to jail for their own protection.

The situation cooled down in Buffalo, but in New York, a week later, an apparently more organized uprising took place. In three days of draft offices were looted and burned, the mayor's house ransacked, and 30 blacks were hanged, shot, or beaten to death by mobs.

For all these reasons, the canal District (which later became known as Little Italy, with its own historical contributions), the Union Block and Dug's Dive are important parts of Buffalo's heritage. Sites like the Union Block, its possible links to the Underground Railroad, and the urban geography and street life o the Canal District are worthy of intensive scholarly study. Still, this history is easily forgotten or misremembered without tangible evidence, such as that unearthed this summer.

The Union Block was torn down around the turn of the century last century. However, since nothing was subsequently built on the site but temporary shacks, the chance still exists to save and perhaps reconstruct this site.